Click here for Part 1

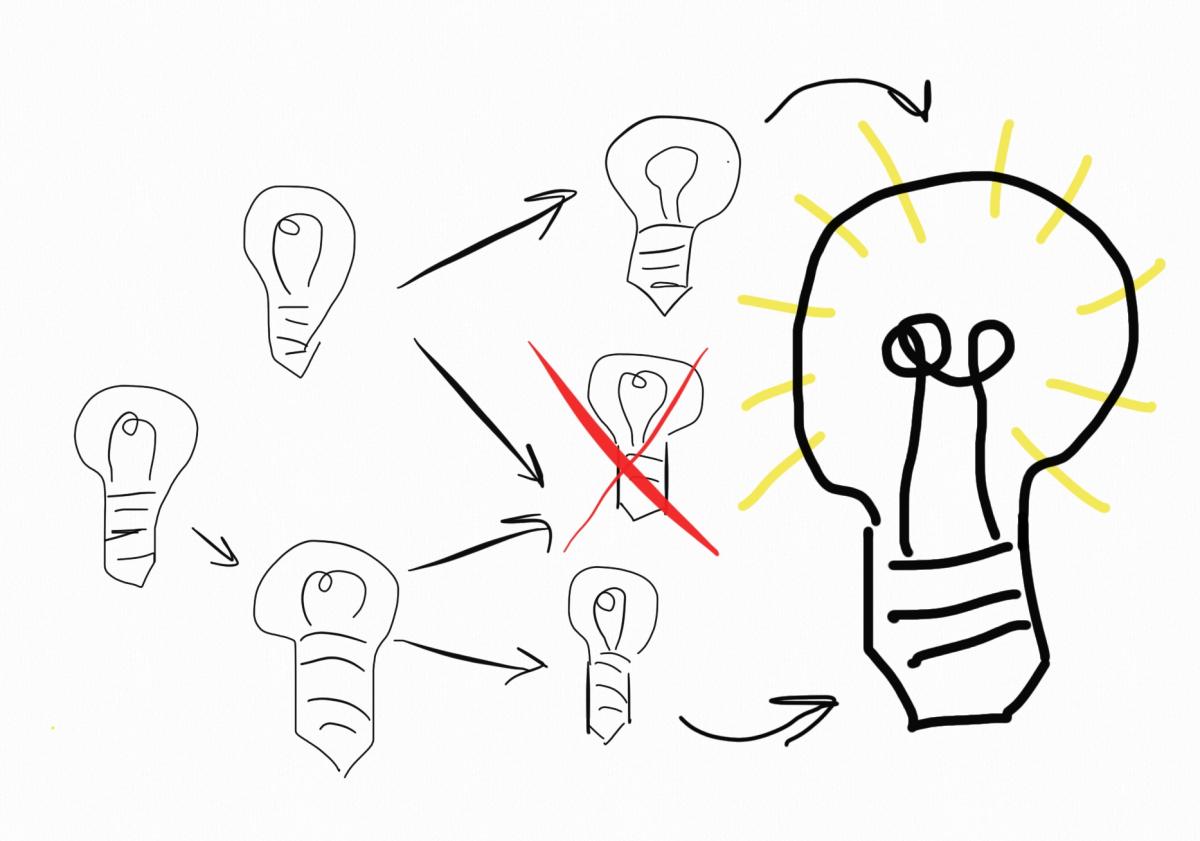

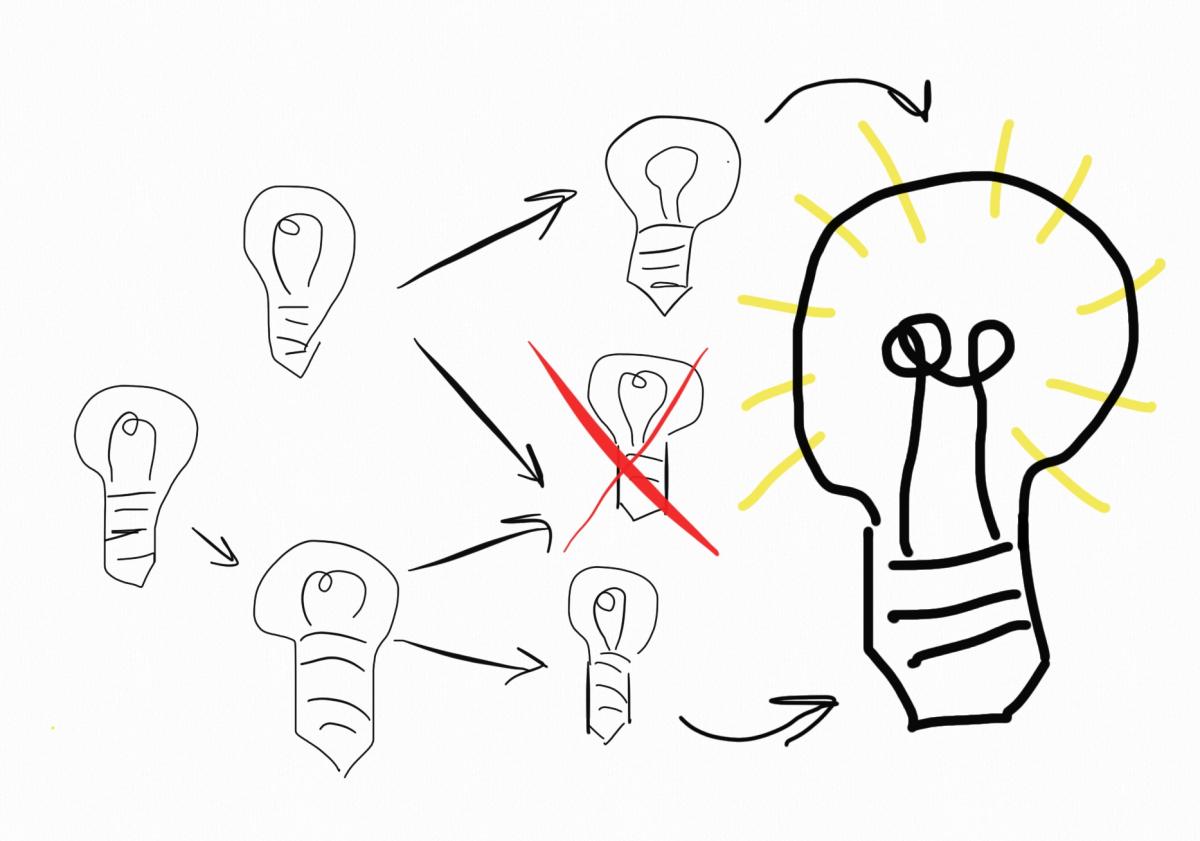

In last week's blog post I highlighted two concepts that I found essential to promote creativity. The first is how improving your technique will enable you to have the ability to express yourself fully. The second concept is recognizing that most ideas are bad and you're probably doing "it" all wrong.

Let's look at the second premise first. The process for design is never linear. Also, people have many different motivations and inspirations for their initial germ of an idea. One person may have an idea of a table whose most important feature is that it seats 10 people. Someone else may want a table whose most important feature is a glass top. A third person might be on a really tight budget and just need a small table for their apartment. These are all perfectly valid approaches to starting a project. Everyone wants the result to satisfy. I'm sure that the initial ideas and the initial sketches for all three of these tables will start out from a completely different places. And that first notion is just that: the first notion. Now comes the real design phase: what does it look like; how do you make it; how much does it cost?

Every designer I have ever met, myself included, starts out with a brain dump. This means, whether you're working by yourself or working in a group, you will need to put down (via notes and sketches) everything and every permutation of things that you can think of. Your goal at this time is to keep track of the dumping brains. This is where piles of notes and sketches make a difference and allow you to go forward. If you are working in a group, the single most important thing is to realize that it's everyone's chance for a brain dump. Every idea gets recorded, no matter how dumb it appears. Analyzing the ideas right away is probably the best way to elicit blank stares and refusals to continue contributing - it's that discouraging. Someone might suggest something that would never work, and they would not bother to mention it if they had more experience. Or someone might suggest something that actually could work in a fresh new way - and the proposer has this idea only because they don't have experience doing it the regular way. It's only once you get everybody's ideas out in the open and on paper that you can start evaluating them without tripping around in circles. People will feel that as long as what they suggested was acknowledged and written down, their contribution was meaningful even if their ideas were later found flawed.

The best part of this process is as ideas come in and are documented either by words or pictures, you end up with a framework in which the actual thing you're going to make starts taking hold. This probably won't happen at one big meeting, but it will happen over time. I have routinely come up with some notion, and wrote it down and then ended up revisiting it sometimes years later. The whole point of keeping a record is that things don't have to happen in real time. Memory isn't a good record of a brain dump. Time passes. Ideas ferment; people go off and investigate elements of the idea in its current incarnation. New ideas can get added, and people start having thoughtful opinions on the project so far. The process ends when a good design seems to grow out of the suggestion pile. In the alternative, a deadline can force the group to look at the pile, weigh the ideas, and pick a direction. In that latter situation, sometimes what looked like a great notion (and which might rest upon a pile of great ideas) still has enough uncertainly that it's time to move on to another different project.

Assuming the project can go forward, the goal of the creator should be to forge these initial thoughts and collections of ideas into a next step. Find a pathway - perhaps by using available technical expertise - to go to the next step. Sometimes that next step is drawings, sometimes that next steps prototyping, and sometimes that next step is working the phones to find suppliers. Mastering technique and developing expertise is key at this point. This isn't when you have stopped thinking about the design, but if you have done the design process properly, changes in direction won't be that frequent. Imagination guides us on a path to new products. The actual design process is really about taking all sorts of ideas, sorting them, and finding the small bits of gold in a pile of junk. Technical expertise helps make sure we are on the right path, speeds up the process, and helps us process the gold.

In the case of TFWW and Gramercy tools, I like to think we are as creative as we've always been. But as the world has thrown us more curve balls, we have (by necessity) gotten better at technique. We've even gotten better at designing efficiently.

For those of you who enjoy a good video, I can highly recommend the following video on creativity by John Cleese. It certainly explains some of the same ideas I am raising here, but far more eloquently.

N.B. Writing blogs is no less a creative process than anything else and I follow the same procedures. What you are reading is the results of about four different drafts and total rewrites; a final decent draft; a once over and proper editing by Sally; and then some final edits and tweaks. When we look at a finished work, we are usually only seeing the final execution, and not all the steps, mis-steps, and blind alleys that it took to get there.

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

tx.

– Nathaniel Hawthorne

As a psych, this is an area of professional interest for me. Any time you want to run ideas past me, or just discuss the topic, email.

Regards from Perth

Derek

And that learning of new techniques is where I build shop furniture. I’ve tried out a lot of techniques on a build for the shop first, and then once that works, I can apply it to “real woodworking.”